PART 1: Reckoning with Buried History: Elixir of Blood, Sweat and Coal Dust

Someone tied a red bandana around this Charleston, WV miner.

The red bandana was a sign of solidarity for miners during the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921

and again in 2018 for teachers during the West Virginia teachers’ strike.

One summer day in 2017, I was at home in Las Vegas hiding out from an intense dry heat. The kind that turns the sidewalk into a searing skillet by 11 am, too hot for the dog’s paws. On the upside, it turns my frizzy hair shiny and luscious. With the air conditioner humming, I turned on PBS and discovered a documentary, the Mine Wars. It felt like a good way to survive the afternoon. I settled in.

I wasn’t alone. My best friend Oliver, a champagne Labradoodle, was lying languidly by my feet. And, hovering just behind me was Mary, one of the many fictional characters that appear to me from time to time. Mary showed up twenty-five years earlier; a mute girl who shared a story about murders in a West Virginia holler in 1992, struggling coal miners, a town in decline. The story didn’t resonate with me then, but Mary intrigued me. Although I wasn’t moved to write her story then, for some reason, she stuck with me all those years. And, now she seemed interested in the documentary.

As the program progressed, I watched desperate coal miners pushed to the brink by a brutal undemocratic system that placed them and their families in a feudal-like existence. After years of fighting for their rights, 10,000 miners took up arms against the oppressive coal overlords, leading to the in 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain, the largest armed insurrection in the United States other than the Civil War. They wanted basic things: the right to unionize; an end to a brutal mine guard system; safer working conditions; enough pay to feed their families. I was incensed. How had I never heard of it?

I felt Mary’s hot breath on my neck and suddenly realized, these were her ancestors. If I could understand their history, maybe I could understand the strange story she had shared with me so long ago. Something went ding in my psyche, and I knew I would turn my world upside down to write her story.

Before the documentary’s credits finished rolling, I was in front of my computer searching for anything about the Battle of Blair Mountain. Up popped the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum. And thus, my four-year journey began.

Jump ahead to September 3, 2021, to a weekend that merged fantasy with reality. It took my breath away. It was the centennial of the Battle of Blair Mountain. And, I had just completed my debut novel, Reclaiming Grace, informed by that deep history and my very patient character, Mary Wyatt. But the amazing thing was, while making connections for my research into this history, I had found a way to be an integral part of the centennial commemoration. The synchronicity of achieving those two milestones within the same week reverberated through my psyche.

When I think back to that day in Las Vegas, I’d like to say I had this all planned out. But I didn’t. I leapt without a net. I trusted all would unfold as it should. And it did. Miners and their families, historians, archaeologists, artifacts, books, videos, online forums—appeared as I needed them. And that was amazing since so much of the history had been kept buried for so long.

Was it magic? I certainly was not a passive figure waiting for the Miners’ Angel to appear and lead me by the hand. I sold my house, moved back to Pittsburgh, my hometown, made phone calls, sent emails, traveled to West Virginia multiple times, entered an MFA program in creative writing in West Virginia. And, when I learned that a centennial of this battle would be happening several years in the future, I volunteered my services to the Blair100 Core Planning Team. It just so happens I have a background in marketing and major events.

So, magic? No. But mystifying? Yes! Everything I needed and every person important to the novel I was writing became available to me. Had I gone the route of my usual spreadsheet planning, there’s no way I could have mapped this journey—where to go, what to read, who to talk to. Each step was a revelation, leading me to the next and the next. All I had to do was be present, and trust.

The three years working with the Blair100 Core Team allowed me to experience an inner thought process of the region that would have otherwise alluded me. In formulating the messaging around the centennial, we had to nail down what was important to communicate. And what they shared grounded me and the story I was writing:

After years of degrading treatment from the coal operators and local government, the Blair uprising represents a breaking point. The response, a multi-racial, multi-ethnic fight for basic labor and human rights.

Yes, the miners lost the battle. But history shows they ultimately won the war.

This history has been buried for generations due to shame, fear of prosecution and imprisonment on the part of families. And suppression by the coal industry and WV government.

Men and women put their lives on the line for each other, not knowing how it would turn out. Theirs is a story of solidarity in the face of grave danger. They should be honored. Rather than shame, this is a story that can instill pride.

It’s time tell the story wide and far.

The men and women who took part in this historic struggle found hope in the face of certain defeat. And then put that hope into action. My West Virginia colleagues found pride in knowing that. And they wanted others in the region to feel that pride, too.

The Blair100 Core Planning Team

Front row, left to right: Kenzie New-Walker, Project Director, WV Mine Wars Museum;

Christy Bailey, National Coal Heritage Area Authority; K.J. Bryant, Author

Back row, left to right: Kyle Warmack, WV Humanities Council; Catherine Moore, WV Mine Wars Museum;

Erin Bates, United Mine Workers of America;

Initially, for me, this was research for my book. But it quickly became something else. Something deep. Working with a talented and committed group of folks in West Virginia, we offered the region and the world the Battle of Blair Mountain Centennial, a platform for pride, with a kick-off event in Charleston and partner events all across West Virginia, Virginia and Pittsburgh. It surpassed all our hopes and expectations. The concert in Charleston, reflecting the diversity that Blair represents, was sold out. And almost every partner event was standing-room-only. The media were hungry to cover it—locally and nationally, including The Nation and The New York Times.

While those of us were putting on the official kick-off for the Centennial, UMWA President Cecil Roberts led union miners and supporters back into history by recreating the 3-day march that miners attempted in 1921. Back then it was to free hundreds of their brothers arrested and jailed in Mingo County for attempting to organize a union. Those determined miners were stopped at Blair Mountain by the Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin and 3,000 “deputies,” backed by state militia, all in the pocket of the coal industry. A battle ensued that ended only when Federal troops were sent in. The miners, many of whom had served in WWI, were patriotic and refused to fight other service men.

UMWA President Cecil Roberts (center) kicking off the recreation of the 1921 3-day miners march to Blair Mountain.

The miners lost that battle and the union was squashed for 12 years until President Roosevelt passed legislation in 1933, ending the mine guard system and granting miners the right to unionize. Because of these brave men and women and the UMWA, workers fought for and earned the 40-hour, 5-day work week, health insurance, safer working conditions and more.

With all that, you would think this history would be common knowledge, at least for those growing up in West Virginia. But no. The coal industry and the state government didn’t think a battle for workers’ rights told a good American story. In 1920, local educator Phil Conley and a group of WV businessmen, including coal owners/operators, formed the American Constitutional Association. Their main goal was to silence this history so it would not be repeated. The ACA selected textbooks and set guidelines for teachers to make sure the mine wars were not taught. Later, after the passage of Roosevelt’s labor legislation, WV Governor Homer Holt held up publication of the WPA Writers’ West Virginia: A Guide to the Mountain State. One complication for him was inclusion of the history of these labor struggles in his state. He was successful in having all mention removed.

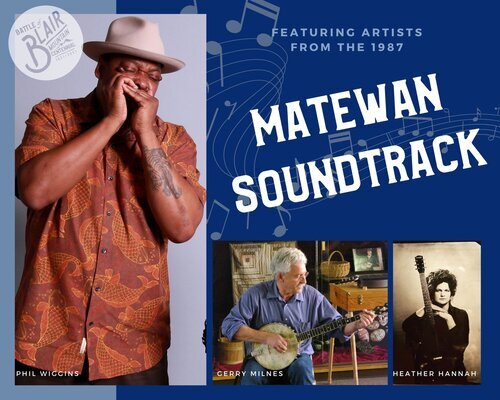

Generations grew up never knowing anything about these historic events. The older folks who had knowledge of there fathers and grandfathers’ involvement were silent out of shame. The miners had lost. Some were killed. Others were prosecuted for treason and murder. And some served prison time. That started to change in the late 1980s when Denise Giardina wrote Storming Heaven, a fictionalized novel about the Battle of Blair Mountain, John Sayles made the movie Matewan and historian Lon Savage wrote Thunder in the Mountains. Interest was piqued, but still nothing was taught in the schools and the general public was not aware of their own history, even right where the history happened.

The formation of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in 2015 brought this history into the community and the schools. When the Blair Centennial was announced, folks from West Virginia and other states far and wide came out. The whispers that had filtered down through the generations in shame now stood proud in the light of day. The Battle of Blair Mountain is no longer buried history. And the region can stand with pride as it learns about a labor struggle that eventually won rights for all workers around the United States, union and nonunion.

So many were deeply moved. Here’s what West Virginia author Ann Pancake said about what the Blair Centennial means to her:

“I felt inspired. I felt hope, and it’s been a while for that one. And I see how you [the Core Team] created the whole weekend and its events, how you’ve made something big and beautiful and tremendously important, in a time and in a place where so much is just being dissolved, taken apart, or worse. You made something.”

Ann Pancake, author of the novel Strange As This Weather Has Been and numerous short stories and essays.

I asked my colleagues on the Core Team, folks with deep roots in West Virginia and some whose ancestors participated in the battle, what the Blair Centennial means to them. They shared this with pride:

As someone not from this culture and with no family ties to the history, it means something different to me. The culmination of four years building friendships, listening, learning, connecting dots. There’s nothing like rolling up your sleeves and working with folks in the trenches, especially during a pandemic, to see what we’re all made of. Together, we shined a light on a history that will never again be buried. My character, Mary, is still with me, now quivering with joy.